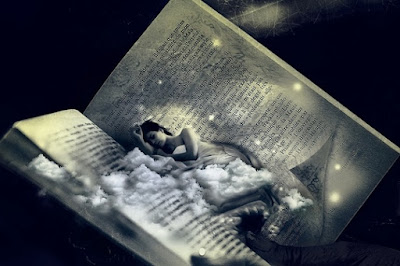

Image by Leandro De Carvalho from Pixabay

By Lisabet Sarai

I've been reading since I was four years old – a total of sixty-seven years. I still marvel at the power of fiction to create visible, tangible worlds. Outwardly, as we read, we look at the words, the sentences, the paragraphs. Blindly, we turn the pages. All the while our inner eyes gaze upon the scenes we construct in response to the author's prose.

A skilled writer can evoke times, places and people with such vividness that, at least while we read, they feel more real than the surrounding environment. As the words penetrate my brain, I see the glare of the sun upon the looming pyramids. I feel the baking heat reflected from the stone, taste the dust kicked up from the bare feet of the passing peasant, smell the steaming dung his donkey leaves in my path. I squirm as the lash scores my bare buttocks, shiver as a fingertip traces the line of my spine, sweat as the girl opposite me on the subway crosses one knee over the other to reveal red lace and tempting shadow. Reading is a sort of miracle that dissolves the here-and-now and crystallizes a totally new universe in its place.

What we see when we read is born of a collaboration between the author and our selves. We bring our histories, expectations and preferences to the act of reading, making the process deeply personal. My images of Catherine Earnshaw in Wuthering Heights, of Anna in Anna Karenina, of Humbert in Lolita, are unlikely to match yours. The author sketches the setting and the characters, but allows us to fill in the details. Even the most meticulous and elaborate descriptions cannot capture the full richness of sensory experience, but imagination embroiders upon the framework of the text and embeds us deep into the world of the story.

One mark of a great writer is knowing what to express and what to leave unsaid. Sometimes the simplest prose is the most evocative.

When I write erotica, I rarely describe my characters' overall appearance. I may call attention to some particular physical characteristic – the elegant curve of a woman's hip, the scatter of curls leading down from a man's navel toward his waistband – but for the most part I allow the reader to create his or her own pictures. Instead of dwelling on what can be seen, I spend most of my time on what can be felt – the characters' internal states.

When I began to expand from erotica into romance, though, I learned that readers of this genre like to have fairly complete descriptions of each major character. They want to know about stature, body type, hair color and style, skin color, eye color, typical clothing... The first time I filled out a cover information sheet for a romance book, I was stuck. The publisher wanted full details about the appearance of the hero and heroine. I hadn't thought much about the question.

Lots of romance authors I know use actual photographs of characters to inspire them. I've adopted this strategy too, in some cases. It's easier to describe a picture than to manufacture a complete physical creation from scratch.

Overall, it seems to me that Western culture is moving away from the imagined to the explicit, and that the written word is losing ground to the visual. These days, video appears to be the preferred medium of communication. If you buy some equipment, you don't receive a user manual any more, you get links to YouTube. My students seem unable to concentrate on any text that does not include lots of pictures, preferably animated. Graphical icons (often obscure to me) have replaced verbal instructions. I really wonder how the blind survive.

Suspense in film – that overwhelming, oppressive sense of imminent danger – has been supplanted by fiery explosions and bloody dismemberings. I personally find the old movies more frightening and more effective. Sex has followed the same trend, in mainstream movies, in advertising and in porn. Everything is out there to be seen, in your face. Nothing is left for the viewer to create. Common visions overwhelm individual interpretations.

High definition television. 3D movies, virtual reality. The thrust of modern technology is to externalize every detail, making everything visible. The inner eye atrophies as imagination becomes superfluous.

The rise of generative AI has only made things worse. AI models digest millions of images, then spit them back out at us, sliced and diced, meticulously detailed but often so stereotyped that it’s easy to tell a computer was involved. I’m getting better and better at identifying AI-generated visualizations, because they tend to look like images I’ve seen dozens of times before.

I remember, back in 2013, when I heard Baz Luhrmann had directed a 3D version of The Great Gatsby, I felt slightly nauseous. 3D dinosaurs in “Jurassic Park” I can accept, but if there was ever a story that needed a light touch, a judicious selection of detail, it's Jay Gatsby's tale. True, Fitzgerald's novel describes at considerable length the wild excesses of the Roaring Twenties, the booze and the jazz, the extravagant parties and casual love affairs. However, all that is just a backdrop to the lonely delusions of the title character and the vacant lives of the people who surround him. You could tell Gatsby's story on an empty stage, with a couple of bottles of champagne as props and a single sax as the sound track.

The result of Luhrmann's misguided (in my opinion) effort was an impressive spectacle with no substance. The film lavishes its attention on the crazy parties and drunken orgies. Meanwhile, Gatsby, Daisy, Jordan and Nick remain ciphers, cardboard characters one can't really care about. You see it all, but feel nothing. That, at least, was my experience.

I sometimes worry that reading will become obsolete, despite the surge in book buying due to ebooks. I'm glad I don't have children growing up in this increasingly literal, visually-oriented world. I'd hate to see them struggling to keep the magic of imagination alive.

Meanwhile, the Luhrmann film had one positive effect. It has motivated me to reread the original book.

.png)